On Friday, we looked at linguistic relativity, scholars Berlin and Kay, and how languages exist in different stages according to how they name colours. To put it simply, their work showed that all humans understand colours in the same way, and that differentiation is not due to culture.

This was considered to be true because the ranges of colours in each language match up across languages. For example, in the Stage II languages we mentioned on Friday, the red they distinguished would fit within the same range of red shades across other languages.

|

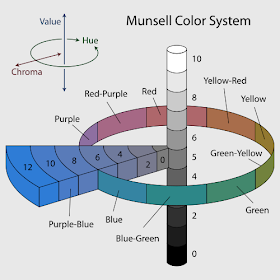

| The Munsell System that was used by Berlin and Kay. |

This means that any given Stage II language should consider "red" to be within the same range as in other languages, regardless of stage, given that they distinguish the colour "red". This understanding of colour and language became known as the universalist view. All colour perception is inherent within humans, so no matter what language you speak, you generally distinguish colours across the same ranges on a physiological level.

The scholars Kessen, Bornstein, and Weiskopf tested this idea using babies, in order to see how they responded to different colours of light. This was done by measuring habituation, whereby you respond less to a given stimulus as you get used to it. For example, you might get a fright if you hear a sudden loud noise, but if you constantly hear sudden loud noises, you barely respond.

In their study, the babies responded more to what we'd think of as distinct colours, rather than different shades or hues of the same colour, just like adults would. This supported the idea that our understanding of colour is with us before language has an opportunity to affect how we think about colour.

Of course, if you're familiar with academia, you won't be surprised to find out that there are ideas challenging Berlin and Kay's work. Their methodology was later criticised by other scholars for being Eurocentric and Western.

While Berlin and Kay thought that the concept of colours was universal, their critics started to side with the ideas of Sapir and Whorf, saying that language does shape how we think. This side of the argument is known as the relativist view.

|

| Russian Blues, geddit? |

If we don't all see or understand colours the same way, how could we test this? An interesting test used native speakers of English and native speakers of Russian. In the Russian language, there are unique terms for what English would call dark blue (siniy) and light blue (goluboy).

English speakers were asked to match a reference colour to one of two choices. If they were what we think of as different colours, they could do it pretty quickly. If they weren't, it took them a little longer. This meant the Russian speakers were quicker at matching their two known blue colours than English speakers were. You can find the study here.

What's the conclusion? A lot of studies support the idea that all of us have the same inherent understanding of colours, and a lot of studies support the idea that languages affect how we understand colours. What's at the end of the linguistic relativity rainbow? Who knows? The debate rages on!

No comments:

Post a Comment